Jejak Seni

On display in the special exhibition currently ongoing at the Malay Heritage Centre (until 21 June) are various objects and facsimiles of written and illustrated colonial accounts of life and industry in the Malay Peninsula and Archipelago, produced between the early- to late-nineteenth-century. These accounts vary from the ostensibly encyclopaedic, such as Walter William Skeat’s Malay Magic, produced following the author’s expedition to the East Coast of the Malay Peninsula between the years of 1899 to 1900, to the seemingly reflective, as in Eugen Von Ransonnet-Villez’s Skizzen Aus Singapur und Djohor (Sketches of Singapore and Johor). Arguable as these accounts may be however, they provide insights into the way that local systems of knowledge within the Malay world were framed and understood to an outsider in the 19th century, as well as the larger social context within which these exchanges occurred. Mystical beliefs and practices, flora, architecture, embroidery, boat-building, and metalware - to name a few - were just some of the practices surveyed as part of this larger pan-European imperialist project to document and collect the world.

Today, however, it is generally acknowledged that these accounts have misrepresented these practices and beliefs. In Maznah Mohamad’s analysis of colonial officer R.O. Winstedt’s ‘Malay Industries’ report in 1925 for instance, she lays bare the cost of Winstedt’s study of boat-building, metal-smithing and textile-weaving in the Federated Malay States: the latter’s emphasis on artisanal value and sophistry comes at the expense of any significant understanding of labour and industry within the Malay world. In other instances, local systems of knowledge are made to accommodate foreign epistemologies. John Crawfurd’s study of Malay architectures in the Malay Peninsula, Java, and Sumatra in his publication History of the Indian Archipelago (1820), for example, is prefaced by the caveat that this study’s sole purpose is to “enable the reader to form a just estimate of [the Malay world’s] social improvement”. Material knowledge in both these instances is thus understood within this context only on account of its value as an ethnographic document.

On the occasion of the Bicentennial, it is worthwhile reflecting upon the legacy of this history on material knowledge today. Practices such as boat-building, metal-smithing and textile-weaving might oftentimes be seen to lie within the domain of craftmanship, on the basis of its social utility. Yet, such practices should also be understood beyond its practical output, in order to consider its seemingly world-making properties - textiles encoded with narratives, for example, or wooden pieces imbued with mystical energies. The continuing use of ‘craft’ and ‘fine art’ as differentiating categories thus suggest the continuing hold of the colonial gaze upon material knowledge, in spite of existing practices today.

In view of this history, the Malay Heritage Centre commissioned 3 artists to produce 3 outdoor installations as part of the special exhibition. Invited to respond to the exhibition’s theme of indigenous and colonial knowledge, the artists created works that incorporated traditional folklore, literature and intangible cultural knowledge as a way of harkening to indigenous modes of making. The following guide presents the works along with the locations of where you might find them, along with exclusive behind-the-scenes peek of their makings.

Artworks

|

1

|

|

Kami Berlabuh ke Garis Magenta (We Docked by the Magenta Line)

2019

Fyerool Darma

With assistance from Azri Azman, Dhiya Muhammad, shif, Hazri, Spegepeng, Khairy and cenderawa$ey

Location: Gedung Kuning, 73 Sultan Gate, Singapore 198497

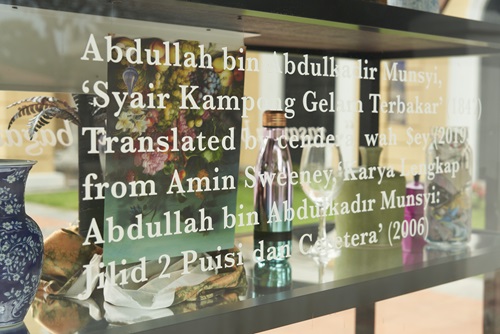

Composed of two vitrine displays filled wall-to-wall with various found objects, this work by Fyerool Darma references Kampong Gelam’s history through a 19th century piece of Malay literature entitled Sya’ir Kampung Gelam Terbakar, written by Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir (also known as Munshi Abdullah). In doing so, the work shifts the axis of Kampong Gelam’s importance away from the larger colonial imagination to that of local public memory instead - specifically, of a great fire that ravaged the district in 1847. The work, monument-like, thus commemorates both the losses incurred by the fire, but also the seeming loss of this history, now buried under the sediment of the district’s transformation in recent years.

|

|

|

|

2

|

|

Sang Kancil dan Pohon Beringin (The Mousedeer and the Banyan Tree)

2019

Shooshie Sulaiman

Location: Lawn, Malay Heritage Centre, 85 Sultan Gate, Singapore 198501

Ninety-nine mousedeers, each approximate in length and height to an actual mousedeer, encircle a pohon beringin (banyan tree) that is taking root in the lawn of the Malay Heritage Centre: this encounter, as imagined and installed by Malaysian artist Shooshie Sulaiman, references both traditional folklore and cosmology within the Malay world. The banyan tree, on one hand, is often seen as a transitional motif in various parts of the Malay world- one that marks the passage from one world to another. The mousedeer, on the other hand, refers to the eponymous Sang Kancil, a mousedeer whose wit and intelligence has been commemorated in various Malay tales. In bringing together the mousedeer and the banyan tree thus, the installation commemorates the spectrum of Malay cosmology and intellect on the historic grounds of the MHC.

|

|

3

|

|

Ke-Datanganku, Dari Laut ke Tanahmu

(My Arrival from the Sea to Your Land)

2019

Nhawfal Juma’at

Location: Kallang Riverside Park

Anchored along the banks of the Kallang River, this sculpture recalls a boat at rest or perhaps on the brink of a voyage. The work is an ode to the vessels that once plied this river, en route to or from the larger Straits of Singapore, as well as the hopes and dreams of the people that these vessels contained. This dual quality of the installation is mirrored in the work’s construction itself, in which mild steel is used on the outside whilst a stainless steel with a mirror finish is used on the inside. Upon stepping into the body of the vessel, the viewer finds themselves reflected against the maritime landscape of the surrounding area. In this accompanying video, the artist shares more about this process of reflection in relation to his own memories of seafaring whilst growing up.

|

|