We know from the impressive surviving libraries of the Javanese palaces in Yogyakarta and Surakarta, that royal courts in maritime Southeast Asia could and did act as patrons and repositories of manuscripts. We also know that much of Malay literature in the manuscript age was produced in and for royal courts—dynastic annals like Sulalatus Salatin and Hikayat Raja-Raja Pasai, epics featuring swashbuckling courtiers like Hikayat Hang Tuah, religious texts composed for royal patrons such as Abudurrauf Singkili’s Mirʾāt al-ṭullāb, syair composed by Lingga court attendants like Encik Kamariah’s Syair Sultan Mahmud. But there are, in stark contrast with the Javanese examples, no Malay royal libraries still in situ (or at least none known to researchers) . Why this should be so is a puzzle that this brief article addresses.

One line of argument is that the Malay manuscript tradition was simply too thin and widely dispersed, and there the were no “bookshops, libraries and the like which are characteristic of the deeper and more fluid manuscript cultures of the Middle East, Muslim India, and classical and late mediaeval Europe”. The surviving manuscript record suggests that this is an overstatement: while they may not have been on a grand scale, there certainly were gatherings of books and readers in Malay court centres.

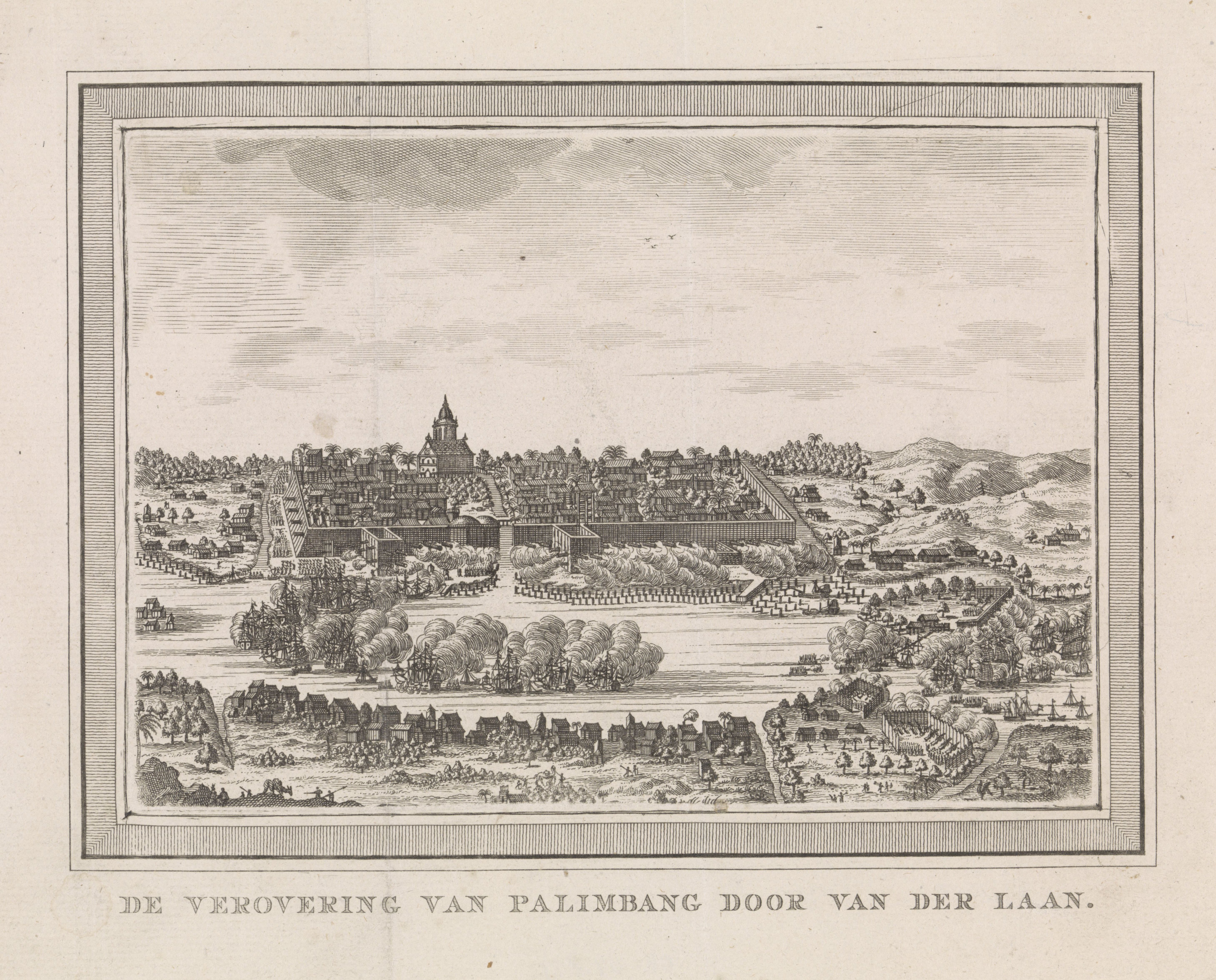

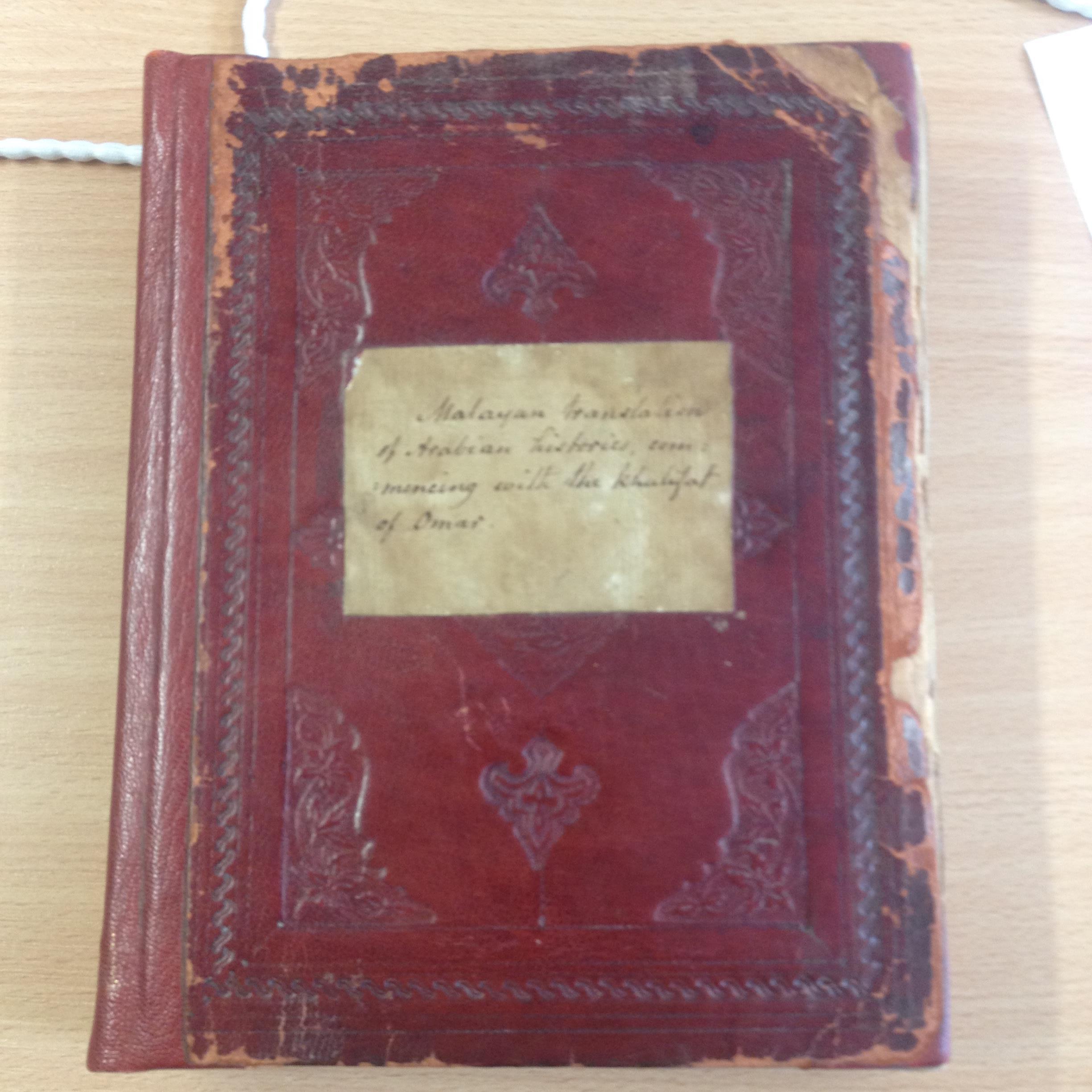

Another obvious answer is that this is due to colonial intervention. It is certainly true that British and Dutch incursions in maritime Southeast Asia profoundly disrupted royal centres of literary production. The most glaring examples are the sack of the Yogyakarta kraton, the attack on the Sultanate of Bone in Makassar,_ and, most significantly for Malay literature, the looting of the Palembang palace. (Not coincidentally, all of these expeditions occurred during Raffles’ command of British rule in Java, 1811-16.) These violent incursions resulted in hundreds of manuscripts entering European private and eventually institutional hands, and presumably many hundreds more manuscripts simply lost. Some 50 Palembang manuscripts can be found in institutional collections in the UK, the Netherlands and Indonesia today. This sole example of a Malay royal library, even if preserved in highly fragmentary form and dispersed across three countries, is fascinating, since it includes examples of texts that speak of a vibrant intellectual culture. Several Palembang palace texts are unique, existing in no other copies, and appear to have been commissioned by particular courtiers, such as the Malay translation of an Arabic historical work, made by Kiai Mas Fakhruddin for Pangeran Ratu bin Paduka Seri Sultan Ahmad Najamuddin (SOAS MS 11505, see image below). Yogyakarta managed to rise from the ashes and its library is today amply stocked. The palace libraries Palembang_ and Bone did not lose all their holdings in the British attacks, since incursions by the Dutch in the following decades brought more manuscripts into European hands. Nevertheless, they must have been considerably weakened as political and cultural centres.

|

|

|

18th-century Dutch impression of Palembang under Dutch siege in 1659.

Image in the public domain.

|

Palembang manuscript with original binding. SOAS MS 11505 |

Violent upheaval during the Second World War and its aftermath may also have played a role in the destruction of palace libraries on the east coast of Sumatra. These were the target of nationalist violence during the Indonesian revolution, including the destruction of the palace of Langkat, and the murder of perhaps the most obvious link between courtly and modern Malay literature, Amir Hamzah. (Amir Hamzah was co-founder of literary journal Poedjangga Baroe, and well known for his style which combined influences from traditional Malay and contemporary European poetry.) But on the other side of the Straits are nine Malay sultanates, most of which suffered little colonial violence, and not only survived but thrived during the late colonial and post-colonial eras. Added to these are the Sultanate of Brunei, perhaps the most lavish exponent of Malay kingship today, and the line of the Johor-Riau Sultanate in Singapore. But none of these appear to have surviving manuscript libraries.

During the century of intense social and political change that preceded Merdeka, literature also changed, moving from manuscript to print, courtly to commercial. The first wave of Malay commercial printing was comprised of large quantities of Riau courtly texts, in part due to the arrival in Singapore of members of the Riau-Lingga court after 1913. Members of this royal family took an active role in developing a new literature. But in the following decades, as Ungku Maimunah Mohd. Tahir has shown, the social background of Malay literature changed radically, with courtly writers giving way to journalists and teachers educated in the new schools. Perhaps most significantly, Malay Sultanates that prospered in the early 20th century seem not to have invested in traditional cultural pursuits, but instead to have sought to remake themselves in a more modern idiom. One might point, for example, to the additions to the Perak regalia made by Sultan Idris I in 1911—not naga armlets or elaborate sireh sets but a diamond tiara and aigrette purchased in London, to be worn to the coronation of George V._ As the material from court literary culture made its way to a mass readership, so the aristocracy seem to have disowned or lost interest in it.

|

| Sultan Idris of Perak with Raja Chulan and Hugh Clifford in London, 1902. Copyright V&A Museum. |

After Merdeka, the newly created institute for the national language in Malaysia, Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, set about acquiring manuscripts. Combing through its manuscript catalogue (1983) yields evidence of the remains of a palace literature as late as the 1960s. Individuals with connections to the royal families of Kedah, Perlis, Selangor, Perak, Kelantan, Riau-Lingga, and Brunei are mentioned as donors or sellers of manuscripts. A Tengku Zamzam appears numerous times as a seller or perhaps dealer in manuscripts, as does Tengku Kalthum binti Sultan Abdul Hamid of Kedah. There are even examples of texts being copied onto foolscap paper, as late as the 1940s—bespeaking a courtly literary tradition that was still, if barely, alive. The result is that the DBP collection has the widest representation of Malay literary texts in any recently archive assembled in the postcolonial era, far richer in this regard than the collection of Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia. PNM’s holdings, apparently amassed in the 1980s and later, when there would have been little left to collect on the Peninsula, have at best two dozen Malay literary manuscripts among many thousands of religious ones (the enormous preponderance of Islamic texts in the Malay manuscript tradition as a whole is an essential and fascinating topic that deserves its own further exploration). Interestingly, a significant subset of these few literary manuscripts that it does hold have connections to the court of Pontianak in Borneo. In the laconic entries of these catalogues, then, we can discern the melancholy, piecemeal dispersal of books no longer of value to their original owners.

While I’ve suggested some reasons why there are no Malay royal libraries like the Javanese ones, this falls far short of a satisfactory account, which would require much more research into the very different social, political and cultural imperatives at work in these two contexts. It is important to note, however, that though there are no intact royal Malay libraries, the displaced and dispersed evidence that we do have shows that gatherings writers, readers and texts did exist in courtly circles. Colonial intervention, it appears, may have played a lesser role in the spoliation of these libraries than the enormous social changes that it, and modernity more generally, ushered in to maritime Southeast Asia. And even from the scattered material that survives, much remains to be rediscovered.

Bibliography

Amoroso, Donna. 2014. Traditionalism and the Ascendancy of the Malay Ruling Class in Colonial Malaya. Singapore: NUS Press.

Ding Choo Ming. 1999. Raja Aisyah Sulaiman: Pengarang Ulung Wanita Melayu. Bangi: Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

Iskandar, Teuku. 1986. “Palembang Kraton Manuscripts.” In C.M.S. Hellwig and S.O. Robson, eds. A Man of Indonesian Letters: Essays in Honour of Professor A. Teeuw. Dordrecht: Foris, 1986. Pp. 67-72.

Katalog Manuskrip Koleksi Perpustakaan Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. 1983. Kuala Lumpur: DBP, 1983.

Katalog Manuskrip Melayu Koleksi Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia (Multiple volumes). 2000-8. Kuala Lumpur: Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia.

Proudfoot, Ian. 2003. “An Expedition in to the Politics of Malay Philology.” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society.

Proudfoot, Ian. 1993. Early Malay Printed Books. Kuala Lumpur: Academy of Malay Studies and the Library, University of Malaya.

Reid, Anthony. 1979. The Blood of the People: Revolution and the End of Traditional Rule in Northern Sumatra. Kuala Lumpur: OUP.

Ungku Maimunah Mohd. Tahir. 1987. Modern Malay Literary Culture: A Historical Perspective. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.